At the latest edition of the Assises de la sécurité held in October 2024 [1], legal issues relating to NIS2 [2] and DORA [3] were discussed at length. It nevertheless appeared necessary to take stock of other regulatory instruments that remain less well known, despite being equally significant. The European Commission’s legislative activity currently shows no sign of slowing, with texts such as MiCA [4], DGA [5], Data Act [6], CRA [7] and the AI Act [8]. Beneath the appearance of a “regulatory layer cake of acronyms”, it is necessary to identify the common thread guiding the European approach to cybersecurity. Examining these instruments through the lens of their underlying objectives therefore becomes necessary.

The European strategy is to establish a harmonised framework enabling economic operators and Member States to harness the potential of digital data and to foster innovation, while safeguarding the security of information systems. This strategy is structured around a number of key principles.

Key takeaways

- The European cybersecurity strategy seeks to establish a harmonised regulatory framework that supports digital development while strengthening security, user trust and user protection.

- The MiCA Regulation and the Cyber Resilience Act enhance user trust by imposing strict rules on crypto-assets and on the cybersecurity of digital products throughout their lifecycle.

- The Digital Governance Act and the Data Act organise regulated access to and sharing of data in order to stimulate the data economy, while respecting the GDPR and European sovereignty.

- The AI Act introduces a risk-based approach to the regulation of artificial intelligence, with graduated obligations depending on the impact of systems on fundamental rights and security.

- Taken together, these instruments provide for dissuasive financial penalties and require organisations to anticipate compliance challenges through strong governance arrangements and enhanced cybersecurity measures.

Establishing user trust

One of the shared features of these various regulations is their aim to promote and strengthen user trust and protection. This is notably the case with the MiCA Regulation (Markets in Crypto-Assets), which forms part of the Digital Finance Package [9]. That legislative package seeks to harmonise the issuance of, and services relating to, crypto-assets, as well as token-based fundraising, by providing a coherent and reinforced legal framework designed to enhance user protection.

Article 3(1)(5) of the MiCA Regulation therefore defines a crypto-asset as “a digital representation of value or of a right which may be transferred and stored electronically, using distributed ledger technology or similar technology”. Article 3(1)(9) adds that a utility token is “a type of crypto-asset intended solely to provide access to a good or a service supplied by its issuer” [10].

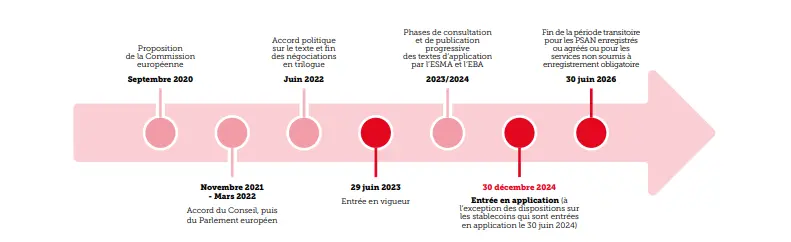

In order to enable financial markets to structure themselves, the Autorité des marchés financiers [11] has published an implementation timetable for the MiCA Regulation.

Accordingly, from 30 December 2024, only crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) that have obtained prior authorisation may provide such services. In this context, the Autorité des marchés financiers warns users against the activities of unauthorised operators and supports service providers in their compliance efforts [12]. One of the objectives of this regulation is to ensure the traceability of crypto-asset transfers in the same manner as any other transaction, in order to combat market manipulation, money laundering, terrorist financing and other criminal activities.

Regarding digital products (software and hardware), the European Commission has also opted for a regulatory instrument. The recently adopted Cyber Resilience Act is intended to establish the framework required for the development of secure products, by ensuring that they are placed on the market with fewer vulnerabilities and that manufacturers remain responsible for their security throughout their lifecycle. To that end, the regulation introduces cybersecurity requirements for products (both hardware and software) covering their entire lifecycle. It sets out a series of specific criteria with which products containing digital elements that are manufactured or distributed within the internal market must comply. All economic operators in the supply chain are subject to these requirements, including manufacturers, distributors and importers. This comprehensive approach represents a new regulatory method. The provisions of this regulation interact with other European instruments, in particular the so-called NIS 2 Directive, which aims to raise the overall level of security within the Member States [13]. NIS 2 establishes cybersecurity requirements, including supply-chain security measures and incident notification obligations, for essential and important entities, with a view to increasing the resilience of the services they provide. As a result, improving the cybersecurity level of products containing digital elements facilitates compliance for entities within the scope of the NIS 2 Directive and strengthens security across the entire supply chain.

Finally, the Cyber Resilience Act seeks to create the conditions under which users can make cybersecurity a genuine factor in the selection and use of products containing digital elements. It therefore constitutes a key regulatory instrument for user trust.

A regulated transparency

The Digital Governance Act and the Data Act both seek to promote access to, sharing and re-use of data within the EU, while respecting the protection of personal data, in particular under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [14]. These two instruments form part of the European data strategy [15], which aims to strengthen the EU’s competitiveness and sovereignty. In other words, their purpose is to establish a harmonised framework enabling economic operators and EU Member States to harness the potential of data and to foster innovation, notably in areas such as health, mobility and climate change adaptation.

On the one hand, one of the principal objectives of the DGA is to encourage public sector bodies to allow the re-use of data and to provide a framework to improve the availability of such data, by fostering trust in data intermediaries and strengthening existing data-sharing mechanisms. The DGA also allows companies to re-use data held by public sector bodies, including so-called “protected data”. Such data may, however, only be re-used subject to certain conditions, in particular that it has been processed in advance so that it no longer contains personal data (anonymisation obligation), and that it does not undermine trade secrets or intellectual property rights. It should be recalled that, under the Regulation, data altruism refers to the voluntary sharing of data by individuals or companies for purposes of general interest (for example, public health or the fight against climate change).

On the other hand, according to the CNIL [16], the objective of the Data Act is to ensure a fairer distribution of the value generated from the use of personal and non-personal data among participants in the data economy, particularly in connection with the use of connected devices and the development of the Internet of Things. In addition, Article 25 of the Data Act seeks to promote competition in the cloud market by reducing barriers to switching from one cloud service provider to another. In this respect, it provides for the complete removal of data egress fees and provider switching charges three years after its entry into force [17].

These two instruments reflect a broader intention to define a harmonised regulatory framework for access to, sharing and (re-)use of data, aligned with the GDPR and the purpose for which the data is used. They must also be considered alongside the European regulation on artificial intelligence and its risk-based approach.

A systematised risk-based approach

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) has increased significantly in recent years and continues to expand across all sectors and types of activity. These uses are not without risk and raise legal issues, particularly in relation to fundamental rights (non-discrimination, respect for private life), the protection of personal data, intellectual property rights and related matters. By establishing a harmonised legal framework within the EU, the European regulation on artificial intelligence (the AI Act) seeks to promote the development of “trustworthy” AI and innovation in the field of AI within the European Union, while respecting its fundamental rights and values (“including democracy, the rule of law and environmental protection […]”) [18]. These objectives are consistent with those of the Council of Europe and of the Council of Europe Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence [19], which aims to ensure that activities carried out throughout the lifecycle of AI systems are fully compatible with human rights.

The Regulation is based on a risk-based approach to AI and introduces a distinction between AI systems according to the risks they pose to “the health, safety or fundamental rights of persons”: unacceptable risk, high risk, and limited or minimal risk. Depending on the risks involved, AI systems are either prohibited outright [20] or permitted subject to specific obligations.

By way of illustration, the AI Regulation sets out specific requirements applicable to high-risk AI systems. In order to be placed on the market, such systems must in particular meet the following requirements:

- Appropriate systems for risk assessment and risk mitigation;

- High-quality datasets used to train the system, in order to minimise risks and discriminatory outcomes;

- Logging of activities to ensure traceability of results;

- Detailed documentation providing all information necessary about the system and its intended purpose to enable authorities to assess compliance;

- A high level of reliability, security and accuracy; etc.

Entities will therefore need to adapt both at the design stage and throughout their internal processes, and to implement a range of mechanisms to remain compliant.

As regards limited-risk AI systems, these are subject to specific transparency obligations, in particular:

- Informing users when they are interacting with AI systems such as chatbots, so that they are aware of the use of AI;

- Ensuring that AI-generated content is identifiable by providers;

- Labelling AI-generated text published for the purpose of informing the public on matters of public interest as artificially generated.

Finally, minimal-risk or no-risk AI systems account for the vast majority of AI systems currently used within the EU (for example, AI-based gaming applications or spam filters). This ambitious regulation will be implemented over several years, and the European Commission intends to secure the support of the various stakeholders. The AI Pact therefore encourages the adoption of this approach within organisations [21].

Thus, although the European approach is based on the adoption of a number of legislative instruments, forming the pieces of a broader regulatory framework, another common feature can be identified: all of these texts provide for significant administrative penalties, following an initial period allowing organisations to achieve compliance with guidance and support from the authorities.

For example, the Cyber Resilience Act provides that, in the event of non-compliance, economic operators may be subject to fines of up to EUR 15 million or 2.5% of total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher. In addition, a product deemed non-compliant or presenting a risk may be subject to restrictive measures, including withdrawal from the market, imposed by the market surveillance authorities designated by the Member States.

As regards the AI Regulation, Article 99 provides that, in relation to prohibited AI practices, administrative fines may reach up to EUR 35 million or, where the infringer is an undertaking, up to 7% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher. Non-compliance with provisions of the Regulation other than those set out in Article 5 may result in an administrative fine of up to EUR 15 million or, where the infringer is an undertaking, up to 3% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

In addition, the provision of inaccurate, incomplete or misleading information to notified bodies or competent national authorities in response to a request may give rise to an administrative fine of up to EUR 7.5 million or, where the infringer is an undertaking, up to 1% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

Conclusion

In conclusion, notwithstanding its complexity, regulatory harmonisation is underway, with clearly defined scopes of application. Taken together, these instruments seek to establish an overarching regulatory framework that ensures citizens and market participants have access to secure digital services, fair competition, enhanced cybersecurity, and respect for fundamental rights, personal data protection and sustainability objectives. Training and awareness-raising across all stakeholders are therefore imperative in order to address effectively the challenges and business opportunities pursued by these texts.

References

[1] Les Assises de la cybersécurité (France)

Annual French cybersecurity conference

https://www.lesassisesdelacybersecurite.com/

[2] Directive (EU) 2022/2555 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union (NIS 2 Directive)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022L2555

[3] Regulation (EU) 2022/2554 on digital operational resilience for the financial sector (DORA Regulation)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R2554&from=FR

[4] Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on markets in crypto-assets (MiCA Regulation), OJ L 150/40, 9 June 2023

[5] Regulation (EU) 2022/868 on European data governance (Data Governance Act – DGA)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R0868

[6] Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act), amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202302854

[7] Regulation on cybersecurity requirements for products with digital elements (Cyber Resilience Act)

Council of the European Union – press release

https://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/press/press-releases/2024/10/10/cyber-resilience-act-council-adopts-new-law-on-security-requirements-for-digital-products/

[8] Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act – AI Act)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401689

[9] European Commission – Digital Finance Package

https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/digital-finance-package_en

[10] Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are excluded from the scope of the MiCA Regulation.

[11] Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF – France)

MiCA implementation timetable

https://www.amf-france.org/fr/actualites-publications/dossiers-thematiques/mica#Calendrier_dapplication_du_rglement_MiCA

[12] Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF – France)

Public warning regarding unauthorised crypto-asset activities

https://www.amf-france.org/fr/actualites-publications/communiques/communiques-de-lamf/crypto-actifs-lautorite-des-marches-financiers-met-en-garde-le-public-contre-les-activites-de-0

[13] The NIS 2 Directive, which will apply from 17 October 2024, is currently being transposed into national law by the Member States. Definitions of key concepts such as “vulnerability” and “incident” derive from this Directive and serve as reference points for defining product security criteria.

[14] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation – GDPR)

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

[15] European Commission – European Data Strategy

https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-data-strategy_fr#gouvernance-des-donn%C3%A9es

[16] Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL – France)

Position on the European data strategy and the Data Governance Act

https://www.cnil.fr/fr/strategie-europeenne-pour-la-donnee-la-cnil-et-ses-homologues-se-prononcent-sur-le-data-governance

[17] The Data Act will enter into force in 2025. On 6 September 2024, the European Commission published a set of FAQs to assist stakeholders in understanding the scope and implications of the Regulation.

https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/commission-publishes-frequently-asked-questions-about-data-act

[18] Recital 1, Artificial Intelligence Act

[19] Council of Europe – Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence

https://rm.coe.int/1680afae3d

[20] Article 5 of the Artificial Intelligence Act (prohibited AI practices)

[21] European Commission – AI Pact

https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/fr/policies/ai-pact

Disclaimer

The opinions, presentations, figures and estimates set forth on the website including in the blog are for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice. For legal advice you should contact a legal professional in your jurisdiction.

The use of any content on this website, including in this blog, for any commercial purposes, including resale, is prohibited, unless permission is first obtained from Evidency. Request for permission should state the purpose and the extent of the reproduction. For non-commercial purposes, all material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is required, together with a link to this website.